Advent of Code 2023

About

Advent of Code 2023 in Haskell. Follow the development of this on https://github.com/alexjercan/aoc-2023. This blog post will contain my notes on solving each day and explanations for the solutions.

Snow effect

Credits to ethancopping for html.

Quickstart

To download the puzzle inputs, copy the .env.example file into .env and

fill in the session with your cookie from the aoc website. Then you can run

./get

To run one day in particular you can run

make Day%

where % is the day number with 2 digits (01, 02, … 20, 21)

For more information on the usage you can also check out the github repository.

Solutions

I will solve each day of AoC in Haskell and post each one on this page.

Credits to Alexandra Radevich for html.

Day 01 - For the first part it is enough to scan trough all the characters

and choose which ones are digits. Then you just need the first and the last.

Combine them into the numbers and add them. But for the second part you also

need to find digits made up of strings, which is more difficult. To be fair, I

think that this first day of AoC was harder than previous years, but it was

still a fun problem. My idea was to generate all the suffixes of the string and

find what digit, if any, starts in the beginning of it. So basically I just

generated all the digits, as before, but took into account the names too. Then

I took the first one and the last one and did the same as for part 1. But I

struggled to implement this idea in Haskell, because I was using the tails

and isInfixOf functions wrong. I tought that tails generates the tail of the

list in the same way as inits does, and starts from the empty list, but it

actually goes the other way around. I found this out after like 20 minutes of

banging my head againts the wall, but it is what it is. Then I tought that

isInfixOf only matches the start of the string, but I should have used

isPrefixOf. Small mistake, I blame ChatGPT for that. Anyway, while working

for the solution for the second part, I realized that you can also solve part 1

with the same approach, but you just ignore the digit names. So yeah, my final

solution is just changing up this tryToDigit function depending on which part

you need to solve. Also, managed to finish part 1 in 02:12 minutes and got

274th place.

Day 02 - Parsing… I kind of forgot how to do it, so I had to check my old

AoC in Haskell and steal it from there. But I am surprised I still remember a

lot of helper functions from parsec. Anyway, my idea was to create a small data

structure called Game that will hold the index and a list of Rounds. The

round will be the RGB colors of the cubes. So I basically started with parsing

from the smallest block and then made my way up to the entire input. You can

go both ways, but I find it easier like this because of whitespaces. I want the

whitespaces to be dealt with in the higher level blocks. After we get the data

structure to parse it is really simple. We just need to check each color of the

round to be bounded by the numbers in the statement and we get the valid games.

Then for the second part, we just had to see what is the minimum number of

cubes required for each game to be able to be played. So we just need to look

for the maximum number in each game and that would be the bare minimum. So

yeah, took me 30 minutes to solve, but most of the time I spent on parsing, you

can also see that from the time it took to solve part 2 after part 1.

Day 03 - Matrices… I always find them annoying in Haskell. However, I don’t think I have found myself in any rabit hole… it was a straightforward solution. My idea was to go trough all the characters on the map, parse all the numbers, then filter just the numbers that have an adjacent symbol and sum them. For part 2 I also kept the position and the character of the symbol, then filtered only gears and then used a hashmap to figure out which gears have 2 numbers (a hashmap from the position of the gear to the numbers that are next to it) and then did the product and sum. It took me longer to solve just because there was a lot more code to write. And in between the first part and second one I took a short break. But I wouldn’t say that this problem was hard. All I can say is that it could have been worse. I liked how I managed to have a really similar solution for both parts.

Day 04 - Parsing numbers. This is something that is somewhat simple in

Haskell. Overall day 4 was easy. Sorting the two number lists and then

iterating them in parallel did the trick for counting the number of matches.

For the second part, my idea was to iterate the card matches once, and update

the number of cards. I used a fold and set the number of cards to be the

accumulator. Each time I get a new card, I use the existing number of matches

to determine how to update the accumulator. Basically just add the number of

cards to the following next matches. I lost like 10 minutes on a small bug, the

cards use 1 indexing, but I forgot that (!!) uses zero indexing. It is what

it is. Haskell is really hard to debug. Or at least I don’t know a good way of

doing it. Also wasted some time on parsing. Even though parsing is easy in

Haskell, setting everything up takes some time.

Credits to Alvaro Montoro for html.

Day 05 - This was a pretty difficult day for me. Took me a lot longer than

usual. Got stuck for a while on the first part. I missed the The destination

range is the same length…With this information, you know that seed number

98 corresponds to soil number 50 and that seed number 99 corresponds to soil

number 51. and I almost did part 2 for part 1, thinking that this is a weird

DP problem :). After I figured out the trick I managed to solve part 1 pretty

quickly. It was just iterating the mappings. My fear was that there will be

mappings that overlap or that the range can be in multiple mappings at once.

For the first part it was fine, but for the second part the fear became a

reality. The idea for the second part was to extend the first function to work

on ranges. So instead of a single number you need to keep track of multiple.

Then I also kept track of the pre and post intervals just in case.

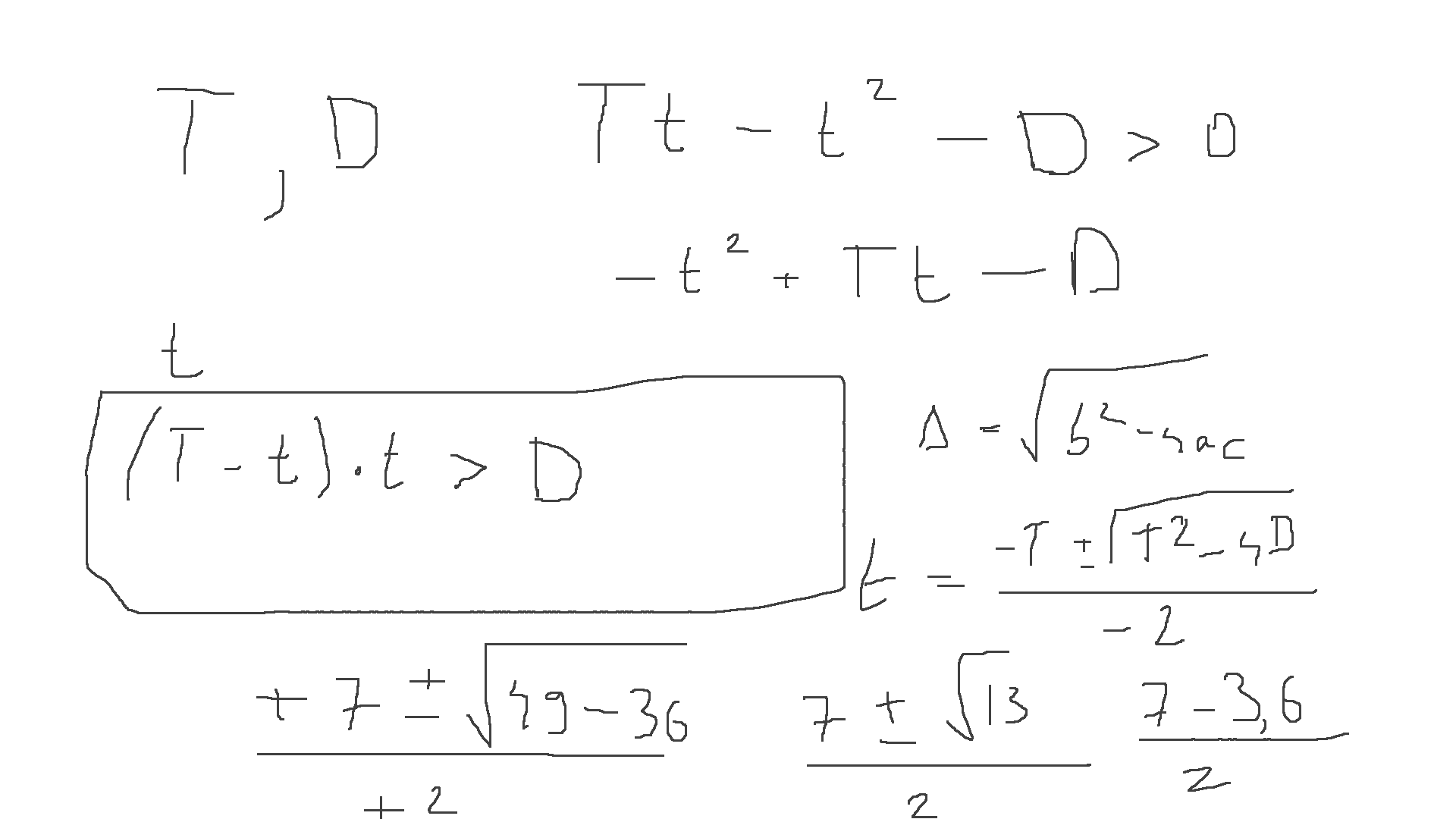

Day 06 - This was a fun puzzle problem. I figured out that there must be a

way to solve it using a formula, and it was. The idea was to get the equation

right. First I tought well, we have the time T and distance D. Then, to get

some speed you need to hold the button, let’s say that time is t. So the

speed is also t, but the remaining time is T - t. This means that the

distance we can travel is (T - t) * t and this needs to be larger than D.

So we have this equation (T - t) * t > D and we can do the quadratic formula

and get the roots for t. And the interval between t1 and t2 is where this

formula holds. This formula will give us the roots -t^2 + T*t - D = 0. We have

a = -1, b = T and c = -D so we have t1,2 = (T +- sqrt(T^2 - 4D)) / 2.

We get both t1 and t2 and then we need to apply ceiling on t1 and

floor on t2. This is because we are interested in the int solutions. One

thing to be careful about is cases where you get t1 or t2 as 10.0 or

similar numbers. Those are the limits where the equation holds for ==, so not

our case > and you need to add 1 or substract 1 more.

Overall it was not that difficult and it was fun to solve. Doable by hand LOL.

Day 07 - This was a pretty fun day to solve. To be fair it was easier than

people predicted. So far even days were easy and odd days were harder. But this

one was at least interesting. So my idea was to sort all the hands. First I

didn’t modify the strings and kept them as I read them, but then I realised

that it doesn’t work because the 10, J, Q, K and A are not in order, so I

mapped them to some other letters, to be higher than all the numbers, but also

in order. To figure out what hand I have, I grouped the cards by value. It was

ok to do it like this, because we only care about pairs and not other special

BS. So yeah that was it for the first part. For the second part, I changed the

J card into a 0 to be the weakest and then did the same thing, but now also

looked at the number of jokers. Depending on it, it can increase the rank of a

hand. It was a bit painful to create the mapping, but that was because I was

trying to cut corners. Don’t cut corners, just do the work once and do it well.

I would say that this problem was one of the easiest ones so far.

Day 08 - When I saw the input, I thought that it’s gonna be a graph

problem, which would have sucked because those are hard in Haskell. But it was

ok, I mean it was a map, but it was not a search. It was pretty straight

forward. I just had to implement a fold until, but that was not hard. Then for

the second part I figured right away that it was a lcm problem. Because in the

example 2 * 3 = 6, but also because it is cycling, which makes sense. What

was nice was that the second part was totally different then the first part, so

IDK if someone would have guessed it. So yeah. I mean I was a bit thinking

about the fact that ZZZ still had options, but I mean… I didn’t think much of

it. I wouldn’t have guessed. I was maybe thinking of like some cycling for

part2 like maybe after how many steps it cycles. But wait. how did lcm work

tho? Like it is not guaranteed that it will cycle with LCM, but it did…

interesting. Well, I guess the map was made in such a way it will work, so it

is what it is. Still nice problem. It would be hard to solve it for real tho…

like if the map would not cycle. But it was a good one.

Credits to Sid Rao for html.

Day 09 - For the first part I have notices that if you sum up all the last

elements of the diffs you get the prediction. For the second part I knew there

was something similar, but it doesn’t look as good in my code. You have to

subtract from the current first element the accumulator. So for the example the

computation would look something like (10 - (3 - (0 - (2 - (0))))) = 5. This

was an easier day, even if it was a weekend day. Which is nice. The solution

was intuitive and the second part made sense. I would like to refactor the code

a bit and get it to look better. But I think it might not be possible to do

with a single function. Maybe I can use fold for both of them and use a folding

function for each part. That can work in some way. The easiest method is to

use a sum function and a diff function in the foldl so yeah. It is possible to

refactor. Nevermind, the easiest way to solve part 2 is to just reverse the

numbers and then use part 1 for it.

Day 10 - The first part of this day was simple enough, after parsing the map. You just need to run BFS and you get the length of the cycle. Then divide it by half to know the maximum distance you can be from the start. The hard part of this day was checking if the tiles connect. I wrote a mapping function checking all the edge cases. It is something like 50 lines of code of pattern matching. Each branch checks if two pipes can connect given the direction they are placed. With this function you can easily generate all the neighbors and perform bfs. For the second part I was stuck, after trying to implement a flood fill solution. I quickly realised that there are cases where the shape could make a loop and the flood algorithm would not be able to detect it. Imagine

..........

.F--7F--7.

.|.FJL7.|.

.|.|..|.|.

.|.L--J.|.

.|------J.

..........

In this case, there are two points that are outside of the shape, but the flood would not reach them.

For the second part I found one hint that helped me. If you cast a ray in a

random direction, you will hit an odd number of edges, when you are inside the

shape, and an even number if you are outside. At first I tried to use up down

left right directions, but this created a problem with colinearities. So I saw

this comment

https://github.com/OskarSigvardsson/adventofcode/blob/master/2023/day10/day10.py

which made use of a diagonal raycast. This way you don’t need to worry about

vertical pipes in you raycast (or horizontal), but depending on the direction,

say from top left to bottom right, you need to be careful about 7 and L

pipes, which should not intersect with the ray, since they are tangent. To

optimize the solution, I used a hashmap to store the number of intersections

and started the search from the bottom right, to be able to fill it in.

Day 11 - For day 11 I wanted to be smart and solve it with A* and set that the costs to travel trough the expanded space is equal to the size (2), but it was too slow. Then I realised that you can also do the manhattan distance to get the path size, since the map has no obstacles. Also with the idea that the expanded space had higher cost. It was basically just the heuristic function, the path itself was not needed. What felt nice was that I almost instantly knew that part 2 will be just an absurd number for the expansion, and it was 1000000; And the best part was that using this manhattan distance computation actually worked for both parts. First I had to compute the distance between the 2 points. Then I counted how many expanded rows and column are between the two points. To get the cost I multiplied the number of rows and columns with the factor minus one and then added it to the manhattan distance.

Day 12 - This was a harder day for me. I started out with a really dumb

solution for the first part. It was just a recursive algorithm that would check

all the possible branches. In some way I expected that the second part would

require a more optimized solution because this was a really dynamic programming

problem. For the second part the simple solution would not finish, so I had to

figure out another solution. My idea was to get a hashmap involved so that I

have a cache, but I couldn’t figure out how to do it. I saw a hint on the AoC

reddit for it though. The idea is to generate the dp hashmap lazily by doing

dp = [... calls to the function ...] and then to define the function that

depends on the dp hashmap. I did this and used the same function that I have

create for the first part, but instead of recursive calls, I have accessed the

hashmap. The hashmap was a pair from the substring that you want to match, the

number of items in the current group and the remaining counts to build the

springs with. The value of the hashmap was the combinations that you have. This

is still not as fast as I think a Python algo can be, but it solved the problem.

It takes around 12 seconds, which is almost 4 times more time then all the

other days combined.

Advent of Code 2023

Credits to Net Ninja for html.

Day 13 - My idea from the start was to implement the mirroring just for

vertical reflections, and then use transpose and reverse to rotate the map and

use the existing mirroring. The simplest way of checking for mirrors was to

split the map at index i, and i should be from 1 to length - 1, to have

at least on row. Then, checking if the sides are the same is just a matter of

reversing the first part and checking if it is equal to the second one. In

Haskell we can use zip to trim the longer part of the chunks and check only

the common part. Then we just need to rotate the map around 4 sides and then

compute the solution from the index that creates a reflection. For the second

part I just modified the mirroring check to allow for one diff between the two

chunks. The condition has to be == 1. We have one mismatch. This didn’t feel

exactly clear at first, I thought it was at most one mismatch, but it actually

was only one. Then updated both parts to work with this type of checking, for

part 1 I used == 0 and for part 2 I used == 1.

Day 14 - I decided to try and solve this day in the easy way, so I just

simulated step by step how the stones would move. I implemented a function that

slides them north and then for the second part I knew that moving left right

and down would be needed. So this way I just had to transpose the matrix (and

or reverse) to rotate it and then use the same simulation function. This works

by folding over the lines of the matrix and building a new one. I took the

last row of the matrix and appended the new, by updating it bases on how the

stone would move. So that means that it will be able to move only one step at

the time. I think that it would be too hard to move the stone all the way in

Haskell. So I just ran this simulation until the matrix converged and did not

change anymore. Then it was just a matter of counting the stones on each line.

For the second part, I immediately knew that it is a cycle finding problem. So,

I tried to simulate 100 steps on the sample input and saw a cycle. Then I tried

to implement it using a function. This meant I had to find the prefix of the

cycle and the cycle. I got the cycle by using the iterate function and then

searching until I found a matrix that repeats itself. Then it was just a matter

of using the formula (1000000000 - length pre) `mod` length cycle to get

the index in the cycle that is going to represent what position we are in at

the end. Then just use the same load as for part1 for that matrix.

Day 15 - This problem was straightforward. First part I just had to map a hash function over the input strings. The second part was basically implementing a hashmap with insert and delete operations. For the second part I used a parser combinator to create the operations that are used in the hashmap. Then I used a vector to keep all the buckets of the hashmap and modify them according to the rules in the statement.

Day 16 - For part 1, the trick was to not get into infinite loops. I did that by removing the visited cells from the newly generated ones. For part 2 I wasted a lot of time trying to implement an efficient solution using caching. But I couldn’t get rid of the infinite loops there. I tried to use a hash map that maps from (row, col, direction) to the set of visited cells. Then I realized that brute-force solution is actually fast enough to try it. So yeah, would have liked to fix my dp attempt, but if it works it works.

Credits to Alexandra Radevich for html.

Day 17 - This day was one of the hardest for me. I knew from the start that

it would require some sort of path finding algorithm and I had a Disjktra

implementation already done for last year (I meant 2021). So I copied that, but

wasted a lot of time trying to figure out how to check if the 3 points are

collinear. I knew for sure that the next part will ask for something like 10

points, so I tought that I should find another way to do it. The better way is

to keep the direction and the “speed” of the crucible in the state. So my state

was ((row, col), direction, num_blocks). This way I can easily generate the

neighbors, either by steering and reseting the speed to zero or continue and

increase it by one. Then the first part became really easy. It was just a

matter of calling the dijkstra function. For the second part, I just updated

the neighbors function, to check for 10 and to a minimum of 4 before turning.

But I kept getting an answer too large. Looking at some solutions I figured out

that the crucible can actually start by going down first, it was not mandatory

to start to the right. So that fixed my issue, after a few hours of struggle.

All in all this felt like the most difficult day so far, but it is also one of

the cleanest solutions, because of the Dijkstra algorithm that I had lying

around.

Day 18 - This was an easier problem. For the first part I managed to get it done in under 15 minutes, which put me in the top 500 place. My idea was pretty basic I would assume. I used a flood fill algorithm. First I generated all the points in the perimeter then used flood fill to count the points that are inside. Of course this didn’t work for part 2 (I didn’t even attempt it since the number of points was huge). I had a hunch that there should be a formula for computing the area of this polygon, but I didn’t know any. I found out by randomly searching that there is indeed one called the shoelace formula. With this new method I generated all the vertices and then applied it. Had a off by one error, but managed to fix it because I already knew the answer for the first part. Not knowing this formula made me lose a lot of time on figuring it out and for the second part I finished after one hour.

Day 19 - For this solution I wanted to use Parsec and create a nice data

structure. I spent most of the time it took to solve this creating a parser,

but in the end it was worth it. For the first part I had to just run the

workflows on each part. Had a hashmap from the name of the workflow to the

rules and each rule had a condition (less than or greater than) and the next

workflow. Pretty much a turing machine of some sorts, that only has

transitions. Then used the parts to compute which are accepted. For the second

part, since there are too many parts to test, I decided to use a similar

approach to day 5 and use intervals. Then start from the in state and split

or trim the intervals that we have. If a condition is always true then we keep

the interval and the next state. If it is always false then we try the next

condition. And if it can be both, we split the interval into the true one and

then continue with the next condition for the one that is false. This solution

worked and was decent in terms of speed. Much better than testing all 2.56

billion cases.

Day 20 - I used again Parsec to create a data structure for the modules. I also used the State Monad to keep track of the global state of signals, although it wasn’t really necessary. In the global state I kept the status (on/off) of the flip flops and the outputs of the parents of the nand gates. With all of that, part 1 was just a matter of simulating one step at the time and then doing it 1000 times. For part 2, as many other have found out, you can actually look at your input to try and optimize the search a bit. I am not sure if my solution works for other inputs, but I had “rx” connected to one nand and then that connected to 4 nand gates. So that meant I had to do LCM on the number of presses to get a low signal on the 4 nand gates. To make the solution a bit more generic, I computed the parents of the “rx” module. Then got the parents of those modules and did the simulation on them (they need the same signal as “rx” and then LCM) and then took the minimum of the parents of “rx”.

Day 21 - Part 1 was pretty simple. Just implement a BFS algorithm and count all the points you visit. The second part was one of the hardest in this year. I knew that somehow the idea is that the pattern will repeat itself or there will be a reccurence, but I coulnd’t fint it. Based on some answers in the mega thread on reddit for this day submissions, I saw that there are some patterns in the input that would indicate that the number of visited cells would be a function. But I still couldn’t figure out the formula. The idea was to simulate for a few steps and then based on this formula you would get the number for the entire input.

Day 22 - This was really hard in my opinion. I combined a bit from the day

14 with moving things around a map. So my solution is similar to that, in the

sense that I used the same fold style. But this time I compared each block to

all other blocks. I tried some other things, but this was the easiest way to do

it. After spending ~4 hours on the simulation and making sure it is correct I

was able to solve both parts rather quickly. I have created two graphs,

supported and supports. The supported graph shows which blocks are

supported by the key and supports shows which blocks support the key. With this

information you can find out which blocks are being supported by the current

one. Then you check each of those blocks to be supported by at least 1 other

block. If that happens for all the blocks that are supported by the key, then

you can delete it safely. For the second part, you just need to recursively

delete the node from the supported mapping and then for each block that was on

top of the current one do the check. This will delete them recursively. I

managed to do this using the state monad. Keep in the state monad the two

mappings. You need to modify only supported tough. So supports could be a

Reader instead, if you really care about that. Overall I liked the solution,

but it was a really difficult problem. Probably easier than day 21 part 2,

which I don’t know if I would have been able to solve alone.

Day 23 - For part 1 it was fairly easy to get it working with a simple DFS,

but the same solution was not working for part2. Probably the restrictions from

part 1 were good enough to create one single corridor for us to follow, but for

part 2 there might have been some cycles as well. After a lot of struggling, I

have managed to implement a function that converted the map from a set of

points to a weighted undirected graph. The vertices of the graph are the

intersections cells, any cell that has more than 2 other neighbors, regardless

of the symbol <^v>.. The weight is the number of cells between the two

intersections. After I had this new data structure, I struggled again to use it

efficiently. I suspect I had some bug in my new DFS code, but after a lot of

messing around I managed to get it to run properly. Something that I find

really hard to do in Haskell is to keep track of the visited nodes correctly,

the recursion really messes up these sets most of the time and it is easier to

use the State monad sometimes. But in the end the solution was ok and was

faster than I expected, only 10 seconds for part 2. I would say that the idea

for the algorithm was not hard to find, but actually implementing the code was

the hard part.

Credits to lirikklimov for html.

Day 24 - Good luck working with floating numbers in Haskell. I wasted so

much time on this bug. I don’t even understand it. I just decided to use

Integer instead of Double, even though I needed floats, and it just worked.

Magic. My guess is that the numbers were too big and also required too much

precision and doubles were not a good option. And the Float type would not

work either because the numebrs were more than 32 bits. I also guess that the

floating decimals were fine to just cut off since it worked with int numbers.

As far as I know Integer is the BigInt equivalent from Java. You can just

make a number as big as you want., but it doesn’t have decimal places. Well…

for part 1 I copied the solution from stack overflow. I tried to figure out by

myself how to compute the intersection of two lines when I know two points, but

StackOverflow had the solution all along. For part 2, I still haven’t done it

yet, and it looks really difficult. Probably brute force? But how? I might need

to extend the intersection function to 3D, which I think I know how to do. But

then what? You cannot just generate all numbers. It looks like we need some

sort of interval and making the search space smaller somehow. We only need the

position and not the velocity of the stone. But to figure out the starting

position we need the speed, right? I mean it looks really hard. Yeah, it would

have been really hard, but by using z3 it was really easy to solve. You only

need to find the right equations for the collision detection and then it is

simple.

Day 25 - This is an amalgamation of the karger’s

algorithm and some random

things I added to keep track of each components. Basically, I kept as an

additional state a mapping from one node to the other nodes inside it’s

component. Initially this was a mapping from a -> [a], but each time a node

gets deleted due to a contraction, I convert it to a -> [a, b] where b is the

node that was deleted. By the end of the execution we will be left with the two

components, the cut size and the nodes in the said components. If the cut size

was 3 then we have the 2 components that we are after, so we can get the length

of each list and multiply them.

Conclusion

This year I have used Haskell to solve all problems from AoC. My best attempt to get on the leaderboard was on the first day where I got the 274th place. I also managed to solve all problems in less than a day. Usually took my at most 5-6 hours to finish the hard problems. There were less search graph problems, which made the things simpler in Haskell. Overall it was a lot of fun as usual.